Your students are now feeling good about crafting their summaries for Writing Question 1. That means they’re halfway to conquering what’s arguably the most intimidating part of the TOEFL exam. Ready to help them take on Writing Question 2?

Unlike Question 1, in which students only needed to summarize someone else’s opinion and avoid stating their own, Question 2 requires students to take a personal stance on an issue and write an essay that supports their argument. However, the overall strategies here are quite similar: help students understand the prompt, give them a clear formula for brainstorming and structuring their response, and teach them some useful language unique to the task type. Easy!

Writing Question 2: details of the task and how to understand the prompt

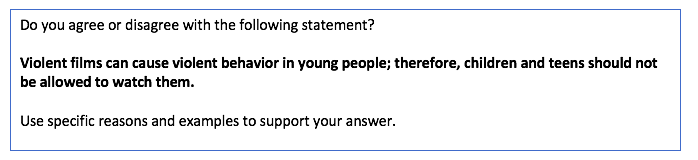

The prompt for this task will be presented in one of two forms. Test-takers may be given a statement and asked whether they agree or disagree with it. For example:

For this version of the prompt, students should think about the statement for a moment and decide if they agree or disagree, and then write their essay accordingly.

The other type of format for the task prompt is very similar; the test-taker may be given two points of view and asked to explain which one they agree with, as in this example:

Slightly different structure, but more or less the same deal as before: students should consider both sides of the issue presented and decide which one they agree with more.

You’d think choosing a side would be the easiest part of this whole section, right? Everyone has opinions! But that’s the funny thing about timed writing exams—it’s amazing how quickly your mind goes blank when you’re staring at that little timer ticking away in the corner of the screen. Students will likely need a little coaching on how to get over that hump.

To start, it’s worth reminding students that, on the TOEFL writing exam, their actual opinion does not matter. There is no “right” or “wrong” answer when it comes to choosing a side here, and students’ responses will not be assessed according to whether the exam-grader shares their stance. All that matters is whether the argument presented in the essay is clearly organized and well-developed. So when it comes to stating their opinion on the prompt, I always tell my students that if they aren’t sure, or if they can think of good arguments for both sides of the issue, they should just pick whichever side they think will be easier to write about. This probably means arguing whichever side they can think of more reasons and examples for, regardless of what their opinion actually is.

A solid response usually includes several different reasons that support the writer’s opinion. So in brainstorming for this task, it’s important for students to choose a stance they can provide at least three different reasons for.

For example, when I first think about the second prompt above, my immediate reaction is that I do actually think texting has caused people to become lazy. We rely so much on autocorrect, abbreviations, and emojis that we’re forgetting how to actually write to each other. But— that’s the only real reason I can think of. On the other hand, I can think of multiple reasons why texting is a “useful and convenient way to communicate.” For one thing, we can send quick messages to people anytime, anywhere, without disturbing the people around us. Plus, the recipient of a text message can read it at their convenience (as opposed to being interrupted by a phone call), and also, it’s useful to be able to send things like pictures, addresses, and links that are then stored in writing for easy reference. (It’s way easier, for example, for your friend to text you the address of that restaurant rather than trying to give you directions over the phone as you scramble to find a pen.) If I really thought about it, I’m sure I could come up with a couple more reasons to back up my original opinion. But in a timed essay, time is of the essence…so I’m going with the one I could think of reasons for quickly.

This is the mindset you want to get your students into. And this leads directly into…

Brainstorming

A good brainstorming format for this task looks almost identical to the one for Question 1:

Topic:

Opinion:

Reason 1:

Example:

Reason 2:

Example:

Reason 3:

Example:

Students are just filling in their own opinions/ reasons as opposed to someone else’s. Here’s how my initial thoughts on the prompt translate into this format:

Topic: Texting = useful communication or makes people lazy?

Opinion: Texting = useful and convenient for communication

Reason 1: send messages anywhere – even in public

Example: I can text my friend from an Uber or even a theater without bugging others

Reason 2: other people receive and respond at convenience

Example: friend in meeting? call could interrupt, but text doesn’t. + no need to spend time listening to voicemail.

Reason 3: send pictures, addresses, links, etc.

Example: texting address to restaurant > describing directions

One of the biggest mistakes students and teachers make on this task is treating brainstorming like a waste of time. But brainstorming is the key to succeeding on this part of the exam. Yes, it takes up valuable time that students could spend actually writing. Yet once it’s done, the hard part is over: the student now has their entire essay mapped out. No more agonizing over how to start, no more panicking about running out of things to say, no more danger of rambling off-topic. Each line in the brainstorming format is like a stepping stone; all the student has to do now is follow the path. And here’s the best part: even if the student butchers the grammar and misspells every third word in the essay, it is now guaranteed that the response will be well-organized and well-developed-- both HUGE contributors to success on this task.

So how long should students spend on brainstorming? Five minutes is a good target. With thirty minutes for the whole task, that leaves twenty five minutes for writing time, which is pretty damn good considering the whole outline will have then already been constructed. Keep in mind, though, that brainstorming in this style has a bit of a learning curve, and it will take some practice. When coaching students in your lessons, you may want to set a timer for ten minutes at first, and then gradually cut down to five as students get more comfortable/ faster.

Make sure to emphasize that brainstorming is just that—brainstorming—not writing the essay. Students only need to write brief notes here, not full sentences. If you look at what I wrote in the format above, there’s enough by each reason/ example to help me remember what I want to write about, but no more than that. Writing out full sentences will eat up precious time.

One final note on brainstorming: just like it doesn’t matter which side of the issue students support, it doesn’t matter what the reasons are, either. When you read the prompt about texting above, you may have thought of three completely different reasons. That’s fine! As long as the reasons support the writer’s opinion, they can really be anything. So encourage your students to draw on their own experiences and get creative!

Writing the essay

Now it’s time to show students how to turn that brainstorming into an amazing essay. First thing’s first: we need our formula. Here’s what the organization of the essay should look like:

First Paragraph: Introduction

Second Paragraph: Body Paragraph I

Third Paragraph: Body Paragraph II

Fourth Paragraph: Body Paragraph III

Fifth Paragraph: Conclusion

Does this look familiar? If you’re like me, you recognize this as the “Five-Paragraph Essay” format that our high school English teachers relentlessly foisted on us. Surprise! It also works perfectly on the TOEFL exam. The interesting thing I’ve found is that, while this is really common practice in US schools, many international students never learned this. Other countries have different ways of teaching writing. But this structure is exactly the kind of thing TOEFL examiners are looking for. So by teaching this to your students, you’re not just giving them an easy formula for building their essay—you’re also handing them a huge jump in their writing score. Definitely a win-win.

Notice that there are three body paragraphs in this format—these directly correspond with the three reasons listed in brainstorming:

Reason 1 = Body Paragraph I

Reason 2 = Body Paragraph II

Reason 3 = Body Paragraph III

The examples students listed will help give more depth to each body paragraph. Then they just need an introduction and conclusion and…done!

Let’s look more closely at what goes in each paragraph:

Introduction

(3-4 sentences)

Briefly states the topic and leads into the writer’s opinion. The final sentence of the introduction should be the thesis statement, which clearly states the essay’s argument.

Body Paragraphs

(3 paragraphs of 4-5 sentences each)

The first sentence of each body paragraph is a topic sentence: it clearly states the corresponding reason supporting the writer’s opinion (thesis). The following sentences should give more information about that reason and at least one example.

Conclusion

(3 sentences)

Basically the introduction, re-worded, in reverse order. There’s an in-depth strategy for introductions and conclusions coming soon!

This isn’t the only way to structure a high-scoring TOEFL essay. But it’s the only one I teach my students because it’s the most fool-proof. You may read or hear about essay formats that present both sides of the issue, or that leave the writer’s opinion a mystery until it’s finally revealed at the end. Sure, these are slightly more stylized options that, when done well, could also work. But in those formats, there’s a lot more danger of ideas becoming scattered, convoluted, or unclear. The last thing you want is your student taking writing style risks on exam day, when there’s really no extra pay-off. The five-paragraph format is clear, it’s easy, and—most importantly—it works.

Got it? Here’s a quick test. Check out this example essay, and decide whether you think it’s a successful response or not, and why:

I was sending text messages to my friend yesterday. I use my cell phone for many different activities. I make phone calls often and sometimes these are very effective. Sometimes I feel lazy when I use my phone. Also, apps like Uber and delivery services can make us lazy. It’s easy and convenient to text my friends. Many people use cell phones and enjoy their benefits.

Cell phones can do many things. Some of these things are helpful, like ordering food from a delivery service, which is quick and easy. You can also look up directions on Google maps if you get lost, or download your favorite music so you can listen to it on your way to work.

When texting it is sometimes necessary to use abbreviations like LOL, OMW, BTW, etc. This makes sending text messages faster and as long as the person reading understands then this doesn’t cause any misunderstandings with communication. Sometimes, though, older people don’t know these abbreviations and they can get confused. Those people might call the younger generation lazy because they don’t take the time to write out the whole words. But they think young people are lazy for lots of reasons.

I always try to text my friends instead of calling them. Also, I prefer when my friends text me because it’s easier to read my text messages than listen to voicemail. Sometimes I wish my parents and relatives would text more often instead of calling me, because we could keep in touch more easily.

Sending text messages is easy and fun but can sometimes cause confusion for people who aren’t used to it. When people text too many gifs and pictures it annoys me sometimes. Also, sometimes I feel like texting makes me lazy because now if I have to cancel plans or have a difficult conversation with friends, I can easily just send a text and cancel instead of following through on my commitment.

What did you think? If you said this response is unsuccessful, you’re right! True, it is organized into five clear paragraphs, but let’s take a look at why this is not an effective response overall:

Even though it contains five paragraphs and minimal errors, this response does not present and develop a clear argument. Even after reading the whole essay, it’s hard to determine what the writer’s opinion actually is and why he/she feels that way. And there are too many irrelevant references to using cell phones for other things. Remember that everything in the essay should only pertain to what’s in the prompt.

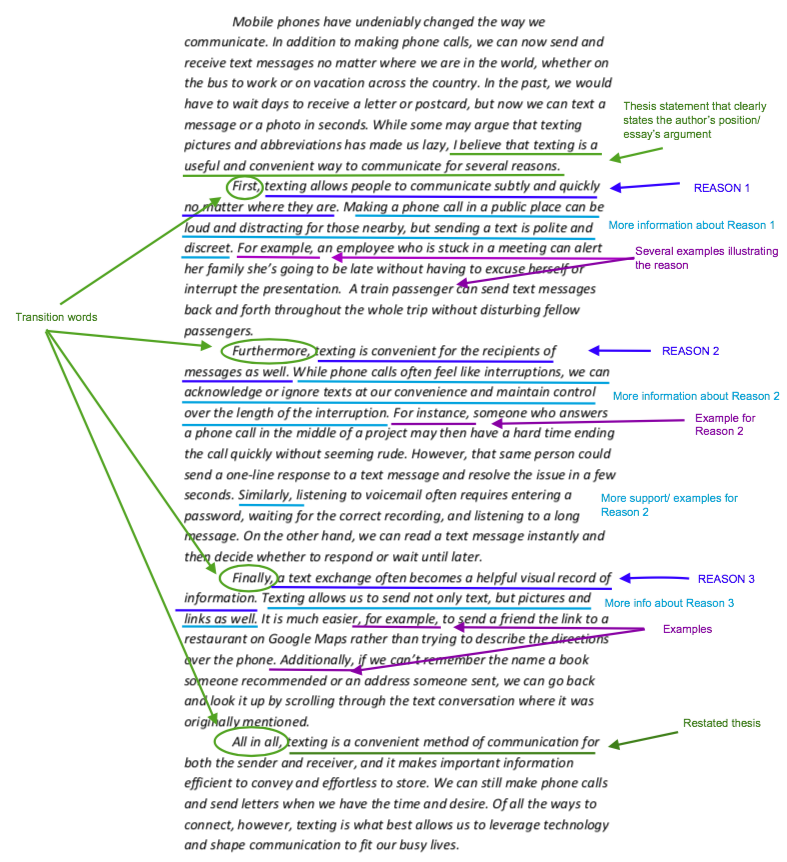

Let’s take a look at a much better example of a response to the same prompt:

Mobile phones have undeniably changed the way we communicate. In addition to making phone calls, we can now send and receive text messages no matter where we are in the world, whether on the bus to work or on vacation across the country. In the past, we would have to wait days to receive a letter or postcard, but now we can text a message or a photo in seconds. While some may argue that texting pictures and abbreviations has made us lazy, I believe that texting is a useful and convenient way to communicate for several reasons.

First, texting allows people to communicate subtly and quickly no matter where they are. Making a phone call in a public place can be loud and distracting for those nearby, but sending a text is polite and discreet. For example, an employee who is stuck in a meeting can alert her family she’s going to be late without having to excuse herself or interrupt the presentation. A train passenger can send text messages back and forth throughout the whole trip without disturbing fellow passengers.

Furthermore, texting is convenient for the recipients of messages as well. While phone calls often feel like interruptions, we can acknowledge or ignore texts at our convenience and maintain control over the length of the interruption. For instance, someone who answers a phone call in the middle of a project may then have a hard time ending the call quickly without seeming rude. However, that same person could send a one-line response to a text message and resolve the issue in a few seconds. Similarly, listening to voicemail often requires entering a password, waiting for the correct recording, and listening to a long message. On the other hand, we can read a text message instantly and then decide whether to respond or wait until later.

Finally, a text exchange often becomes a helpful visual record of information. Texting allows us to send not only text, but pictures and links as well. It is much easier, for example, to send a friend the link to a restaurant on Google Maps rather than trying to describe the directions over the phone. Additionally, if we can’t remember the name a book someone recommended or an address someone sent, we can go back and look it up by scrolling through the text conversation where it was originally mentioned.

All in all, texting is a convenient method of communication for both the sender and receiver, and it makes important information efficient to convey and effortless to store. We can still make phone calls and send letters when we have the time and desire. Of all the ways to connect, however, texting is what best allows us to leverage technology and shape communication to fit our busy lives.

Here's the breakdown of why it works:

This is a good response because it…

√ Is clearly organized into paragraphs

√ Includes a clearly stated thesis (opinion) as the last sentence of the introduction

√ Begins each of the three body paragraphs with a topic sentence, or reason for the opinion

√ Contains examples to back up each reason

√ Restates the thesis as the first sentence of the conclusion

√ Uses language like first, furthermore, finally, for instance, and however to connect ideas and create smooth transitions

To summarize, the key things students need to practice in order to succeed on this task are:

Taking a clear stance on an issue and stating the reasons behind it

Organizing their essay into five clear paragraphs (introduction + three body paragraphs + conclusion)

Using language to introduce and connect ideas